Stories about Shimon Even (by Oded)

| |

|

|

|

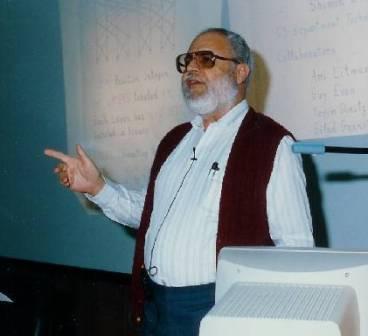

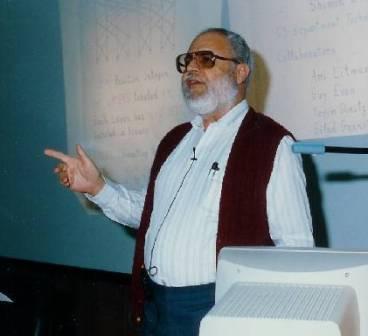

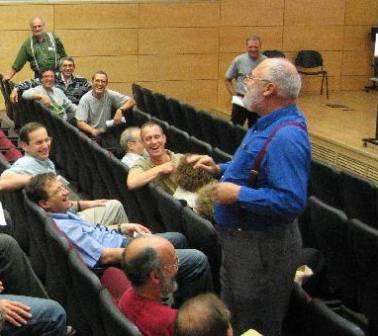

Shimon Even was born in Israel on June 15th, 1935.

He died on May 1st, 2004.

In addition to his pioneering research contributions

(most notably to Graph Algorithms and Cryptography),

Shimon is known for having been a highly influential educator.

He played a major role in establishing computer science

education in Israel (e.g., at the Weizmann Institute and the Technion).

He served as a source of professional inspiration and as a role model

for generations of young students and researchers.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

How do you communicate the fascinating character of a person

to people who were not fortunate to have met him?

One way of doing this is telling stories.

|

|

|

|

|

|

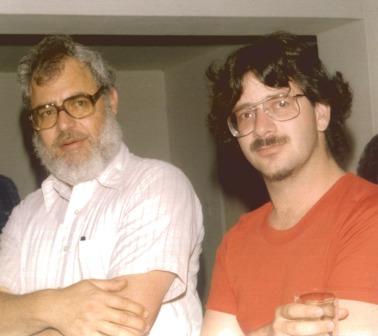

My very first memories of Shimon

The first memories are from his legendary Graph Algorithms class.

I vividly recall my admiration to his style of presenting material;

always focusing on the key ideas and on the underlying intuition.

I was even more amazed by his never-failing ability to "hit the point"

every time he answered our questions (i.e., he would always understand

what is actually underlying our confusion or doubt and respond to it).

He seemed to me the personification of wisdom, indeed god-like.

Needless to say, the thought of being his student had never

crossed my mind.

Half a year later, in the summer vacation after my 2nd undergraduate year,

I was traveling in Europe. I was in London, it was almost 11PM, and the

last Tube was about to leave the center of the city. I ran through the entire

station and entered the wagon with the doors slamming behind me. I almost

fell on a distinguish Lord who was sitting across the door. After a moment,

I told myself "strange, this majestic Lord looks like Professor Even"

and then we recognized each other. It turned out that we were heading to

the same station, and then to the same hotel. So Shimon and Tamar

invited me to their room for a midnight cup of tea. There was a nice

conversation, but this was not the beginning of a wonderful friendship.

He was very friendly and I did notice this fact, but this did not make

me feel comfortable with him. How could I have been comfortable with

somebody I viewed as a Greek God.

Our ways crossed again only a year later. I was selected to be his TA

in that legendary course, and somehow I became his graduate student.

One thing just led to another, or maybe it was only my perception and

he had it all planned. In any case, in spite of all his efforts, I could

never rid myself from the feeling that I was dealing with a (Greek) God.

Throughout all the years that followed, I loved him and I knew he loved me,

but I had to force myself to call him "Shimon" -- even calling his attention

(without calling him by any name) felt too daring.

This is my story. It probably sound weird and says more about me than

about him. But still, I believe that it explains the big paradox of

how come that a warm and open person like Shimon may induce such "fear"

(where by "fear" I mean the Hebrew word used in "fear of god",

a term that is a hybrid of "fear" and "deep respect" and "love").

[May 2004]

A story of intuition

In 1978, as an undergraduate, I attended Shimon's course Graph Algorithms.

At some point, one student was annoyed at Shimon's "untraditional"

way of analyzing algorithms, and asked whether Shimon's demonstrations

constituted a proof and if so what is a proof.

Shimon answer was immediate, short, and clear:

A proof is whatever convinces me.

Many years later, when first seeing the definition

of interactive proofs, I was reminded of Shimon's answer.

I think that interactive proofs are a perfect formalization of

Shimon's intuition: interactive proofs are indeed convincing,

and essentially any convincing demonstration

is actually an interactive proof.

A few years later, I started using Shimon's answer

as a motto for surveys on probabilistic proof systems.

[February 2005]

A story for bad times

Here is a story that seems most appropriate to the current era

in which we (scientists, especially those not at Weizmann)

face administrations (i.e., VERA, VATAT, and the government)

that reason only via money and power...

In the late 1970s, when becoming chairman of CS at the Technion,

Shimon noted that the computer used for teaching was more adequate

for a historical display. He asked for a meeting with the Technion's

president, in which he requested permission to buy a new computer.

The president refused Shimon's request

by saying that the department already has a computer,

and remained unconvinced by Shimon's explanation that

this "piece of junk" is worthless (beyond its junk-yard value).

"For all I know", the president said, "you have a computer".

A week later, Shimon phoned the president and asked again for

a new computer. The conversation went on as follows.

President: I already told you that you have a computer,

so you don't need a new one.

Shimon: But I don't have a computer.

President: What do you mean?

Shimon: I sold it.

President: What did you do???

Shimon: I sold it as junk.

President: Who allowed you to do this???

Shimon: I don't need permission to sell old equipment

(see Technion's Regulations, Article No. NNN).

President: So what do you want now?

Shimon: Your permission to buy a new computer.

President: You are NOT getting it!

Shimon: So I'm not opening the next academic year.

We cannot teach Computer Science without a computer.

President: We'll see about this.

Shimon: Yes, we'll see about this.

I'm not opening the next academic year without a computer.

Well, the next academic year was opened with a new computer...

[February 2008]

A short quote regarding natural problems

One days somebody was presenting to Shimon a problem,

and wanted to proceed to motivated it with a practical application.

Shimon, who cared very much about practice, stopped him and said:

When I see a natural problem I don't care about practical applications.

[December 2008]

Starting and completing research projects

A main characteristic of Shimon,

which made him a role model to many,

is his attitude towards doing research;

and, in particular, his attitude towards starting

and completing research projects.

The starting point for research was always a natural problem,

with clear intuitive contents, regarding efficient computation.

The emphasis here is on the subject matter,

efficient computation, and on the clear

intuitive contents of the question being asked

in the context of this general subject matter.

Regarding the completion of a research project,

this did not occur when the main results were achieved,

but rather after obtaining a deep understanding of

their underlying principles

and providing clear expositions

of these principles to the relevant research community.

[February 2010]

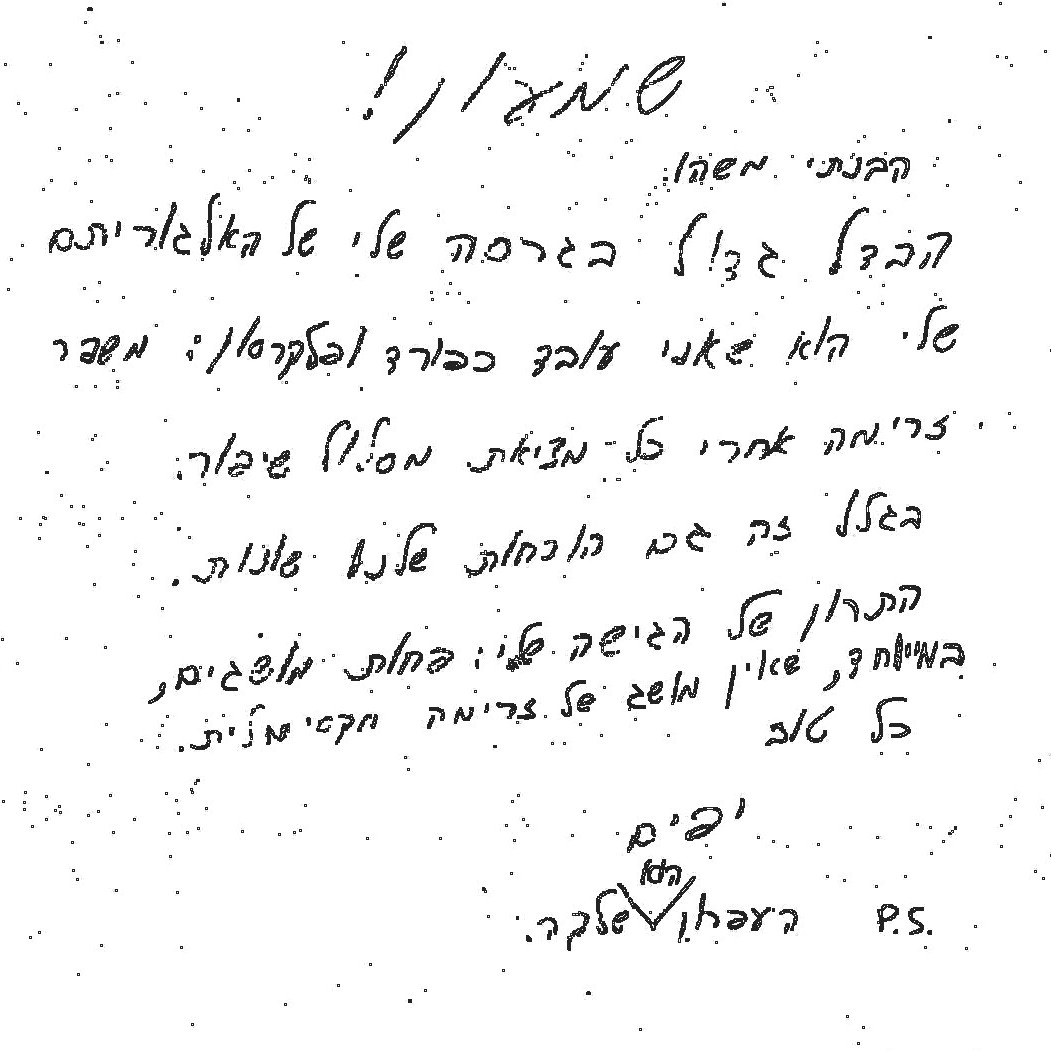

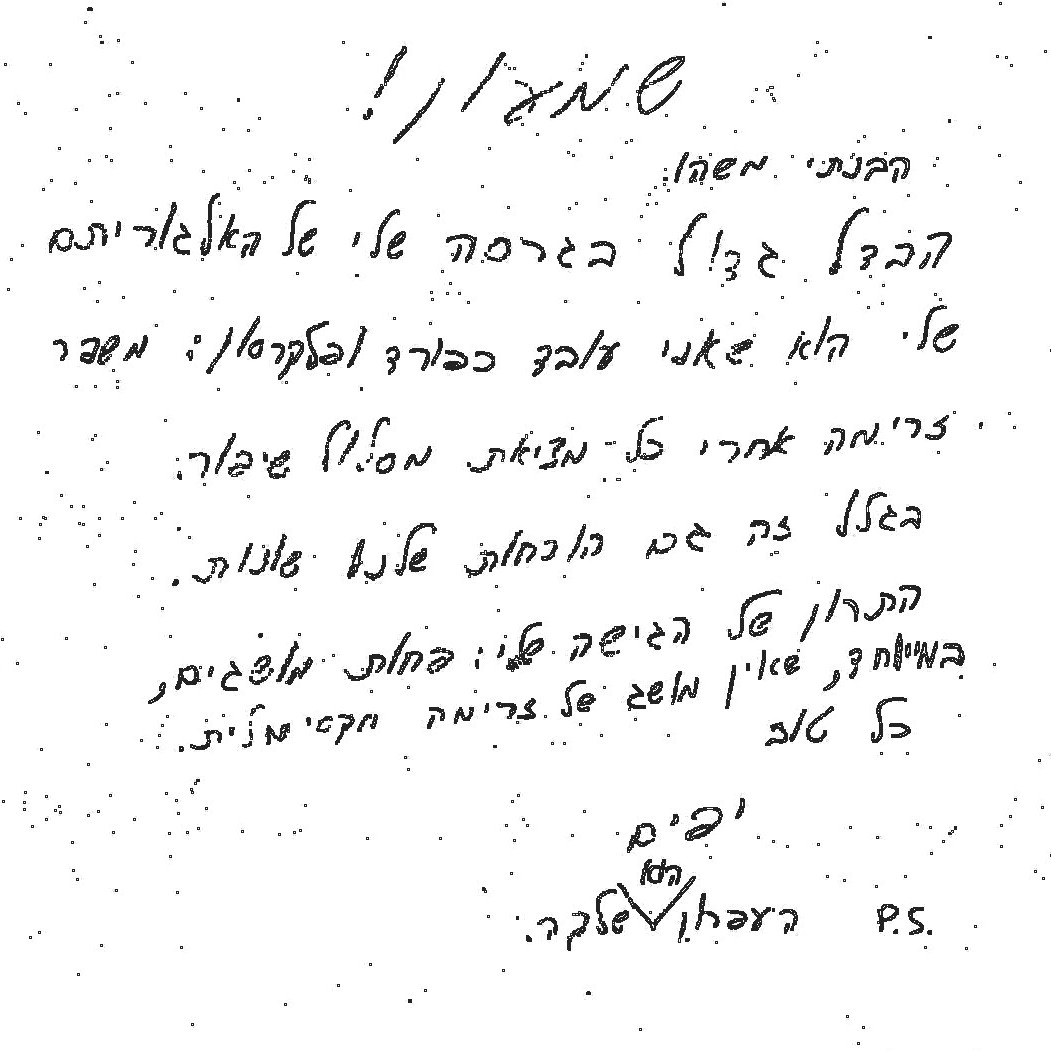

My Take of Dinitz's Story

I refer to a

story told by Yefim Dinitz,

which elaborates on his

note to Shimon,

reproduced below:

| |

|

Shimon!

I understood something.

[The] big difference [between] my version of my algorithm

[and your version of it] is that I work like Ford and Fulkerson:

[I] improve flow after each finding of an augmenting path.

Therefore, our proofs are also different.

The advantage of my approach [is that I use] less notions;

in particular, [I] do not use the notion of maximal flow.

Best. Yefim.

P.S.: The pencil is yours.

|

|

|

This note was written by Yefim to Shimon in the 1990s,

after attending Shimon's lecture on Dinitz's algorithm,

which took place as part of Shimon's undergraduate course

on Graph Algorithms.

I'm sure Shimon did not consider the fact that Dinitz's version uses

less notions (and relies on a more sophisticated data structure) an

advantage; certainly not when an exposition to undergraduates is concerned.

I find this story very typical of Shimon.

Firstly, it is clear that he wanted to understand the algorithm as

soon as possible, and if he could not do it by penetrating the

inventor's mindframe then he just used the clues given by the intentor

to invent his own version. Next, he polished this own version to perfection,

rather than struggling to see how his version fits the original one.

Finally, years later, when having the opportunity to meet the inventor,

he was very amused to learn of the inventor's view of his version.

Thus, although Shimon liked the stories behind the research very much,

understanding the actual contents of the research took clear priority.

[August 2011]

A short quote regarding pluralism

I am not sure if the following description is originally Shimon's,

but I did hear it from him. It refers to researchers that

would understand in five minutes what it takes others months

to understand, but they will never understand more than that.

What I find interesting is that Shimon would express admiration both

to these fast thinkers and to the slower but deeper thinkers that

may surpass them at times. Indeed, in some cases he added this

sentence after explicitly expressing admiration to such a fast thinker.

I took this as a demonstration of the deep pluralism which characterized

Shimon, although it was not evident in superficial encounters with him.

[December 2011]

See memorial page for Shimon Even

and

the legancy of Shimon Even (2014).

Back to Oded Goldreich's homepage.